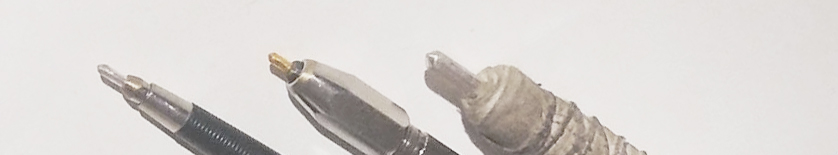

in the anglosaxon countries with more traditional academies, metalpoint is still taught and used. in the netherlands however, the technique is quite uncommon. therefore a small introduction is in place (oddly enough in the lingua franca of todays art world: english). metalpoint is predecessor to the pencil, or in dutch *potlood*, which still has the word *lead* in it. soft metals, like lead, copper, silver or gold are used, though mostly silver, which has the best softness and quality for money ratio.

ground

metalpoint is a drawing technique, in the beginnings sometimes applied on parchment, but mostly on paper. on it, being prepared with a coursing agent like chalk or marbledust, a thin metal rod can be used to scratch lines that cannot be erased. in the italian renaissance, (purple ao) coloured grounds were used with white egg tempera highlights, whereas flemish masters mostly used white or cream grounds.

contrast

the contrast is subject to the type of metal used, but always quite a lot less than most other drawing techniques like graphite or charcoal. although the endresult resembles to the untrained eye that of a pencil drawing, the drawing technique is utterly different. whereas with pencil you can darken the line by applying more pressure, with metalpoint the hue darkens only by carefully building up hatching lines. it feels almost halfway like painting rather than line drawing.

hue

all metalpoints give gray lines with only very slight hue differences. it starts out grey that subsequently discolours due to oxidation (in most cases). lead will turn blueish grey, copper yellowish grey, silver brownish grey, but gold will just stay grey. the ground sands off very small particles, which lose their colour in the violent white light (on a black ground, gold will have a light goldish hue). gold does not oxidate. silver does: a little brownish layer, then stops – unlike iron (silverware turns black instead of brown because of seliva and soap etc). and yes: a gold- or silverpoint drawing really is made out of gold or silver (particles).

renaissance

metalpoint is old, at least used since the 1400s. it was especially popular amongst renaissance artists, like Leonardo da Vinci and Jan van Eyck – though more out of necessity (the pencil having to be invented yet). it was used as a sketching technique and/or to set up paintings (almost never meant as final result – although there has to be said that in the south, paintings were more valued, whereas in the north of europe, with a growingly rich commoners class, drawings were a serious business too).

revival

after the renaissance, graphite replaced metalpoint. the latter was forgotten until the end of the 19th century, until romantic artists and the prerafaellites, digging old crafts, dug up the technique. it is then, that goldpoint became more common, for aesthetic reasons. since, it has been steadily used by a modest number of artists. recently (2010s), there’s a small pickup with several solely metalpoint exhibitions in New York and London.

present

bought directly from the precious metal whole seller, I mostly use 999 silver and 999 gold (or 24 carat). and of course only the best paper (Hahnemühle): it has to endure the wet grounding and then the metal scratching and pressuring without deforming. my frames vary from none, complementary, regular, to the best (Mertens), depending on your wishes and means.bottomless pit (2018), with complementary frame